Almsgiving to the poor is a manifestation of mercy strictly connected to the duties of a good Christian. In some ways, it is also a form of justice, since everyone should have the right to have the necessary to live. Let’s see in which cases it is right to practise it.

Is almsgiving a correct form of charity? Is it right to practise this?

The question may seem trivial, something that is answered without thinking, just like, without thinking, sometimes we happen to casually stretch a handful of change into the outstretched hand of someone asking us for help along the road, or in front of the church. A gesture performed in a hurry, without thinking, or, with equal indifference, not done. In both cases, almsgiving results as something uncomfortable, unpleasant, negative, for those who do it (or don’t do it), and for those who receive it.

Of course, it shouldn’t be so. We must consider the importance that charity plays in the life and faith of a Christian. It is one of the theological virtues, that is those virtues that should be at the basis of the life and action of the man who wants to approach God and live in His word.

“The duty of almsgiving is as old as the Bible. Sacrifice and almsgiving were two duties that a religious person had to fulfil. There are important pages in the Old Testament, where God demands special attention for the poor who, from time to time, are the propertyless, foreigners, orphans and widows” Pope Francis recalled during the Jubilee Audience of 9 April 2016, dedicated to Mercy and Almsgiving.

Charity as acceptance, therefore, availability towards one’s neighbour, the will to put oneself at the service of others, of the poor, of the needy, in the name of a sense of superior justice, of a yearning for what is just, good, beautiful.

Charity and alms in other religions

Muslims also hold this virtue of great importance, which for them is called zakat, and is the third pillar of Islam. The zakat is one of the most important religious duties for a good Muslim and represents a way to pay off the debt that every man has to God for all that is beautiful he has given him. Only in this way can man demonstrate that he deserves those gifts. Indeed, the Prophet Muhammad says: “Charity is an obligation for every Muslim, and whoever does not have the means to do a good deed or avoid committing a wrong one. This is his charity.”

Jews exercise a particular form of charity: the Zedaqah. But what are the differences between Christian charity and Jewish Zedaqah? In a previous article dedicated to the differences between Judaism and Christianity, we talked in-depth about the importance of the Zedaqah in the Jewish religion. It is one of the most essential obligations for a good Jew, so much so that it is one of the three actions with which a man can overturn an unfavourable decree. Indeed, the Hebrew sacred texts state that the Zedaqah can save a person even from death, and in the Talmud, it is written that it is worth more than all the other mizvot (positive and negative obligations for Jews) put together. Again in the Talmud, we read that every time a person applies the Zedaqah, he personally receives the Divine Presence. For the Jews, therefore, the Zedaqah is an instrument of redemption and salvation. What exactly is it? Without pretending to list here the long list of precepts and rules linked to the Zedaqah, we can define it as a form of charity, of almsgiving. For the Jews it is a positive precept, therefore an obligation, to give to the poor in proportion to what is due to them, if one has the faculty to do so, whether they are Jews or non-Jews, family members, friends, strangers. This mitzvah is defined by many passages of the Hebrew sacred texts, where we read for example: “You will keep the stranger, the resident and the one who lives with you” (Lev. 25:35), or “You shall open your hand” (Deut. 15:8).

The differences between Judaism and Christianity

What are the differences between Judaism and Christianity? Is the God of the Jews the same as the Christians? Let’s try to discover together…

However, we must not confuse the Jewish Zedaqah with Christian charity. The two practises arising from completely different assumptions.

The term charity derives from the Latin “Caritas”, love, benevolence. So, simplifying a lot, we can affirm that every form of Christian charity derives from compassion, from love, from empathy towards those who suffer and are less fortunate.

For Jews, this is not the case. The word Zedaqah means “justice”, and it has nothing to do with the feelings that the practitioner has for the one who receives it. A good Jew must necessarily practise the Zedaqah, even towards those who, at first sight, do not deserve it. He has to do it because he should do so.

But how does charity work?

To fully understand the meaning of almsgiving it would be enough to dwell on the etymology of the word itself. The word alms derives from the Greek “eleèo”, I have compassion, and it would serve nothing else to make manifest the true meaning of this word and all that it entails.

Almsgiving is a way to show one’s charity, one’s love for one’s neighbour, one’s compassion. But we must be very careful not to fall into the illusion that it is enough to give material, monetary offer to be at peace with one’s conscience. The efficacy of almsgiving resides solely in the spirit with which it is dispensed, that spirit of charity which should be the basis of a good Christian. Charity should be manifested every day, in many different ways, and only in this way does it become a form of faith, the witness of one‘s will emulate Christ, to imitate his example. This requires commitment, energy, sacrifice because offering one’s availability to those in difficulty, offering not only economic but above all human comfort, takes much more time and effort than those necessary to open the wallet and take out a few coins.

Jesus himself warns us against the wrong way to give alms, motivated only by selfish, superficial, petty reasons. He said to the Pharisees: “You think yourselves righteous before men, but God knows your hearts: what is exalted among men is detestable before God” (Mt 16, 14-15).

Pope Francis adds to the dose: “Almsgiving is done by looking the poor in the eyes, involving him, and thus demonstrating sincere attention to him. Otherwise, it is only public self-promotion, like that of certain Pharisees of the Gospel.”

It is useless to give alms just to wash one’s conscience, to exorcise the spectre of poverty under the illusion of relieving someone else’s state of poverty, to make oneself beautiful in the eyes of others, of the parish priest, of the community. Charity is and must be first of all an act of love, and secondly the recognition of an act of justice: everyone should deserve to live worthily, having at least the bare essentials to do so. God does not want goods to remain in the hands of a few, but that they belong to everyone, to guarantee dignity and survival to everyone. What God created belongs to everyone.

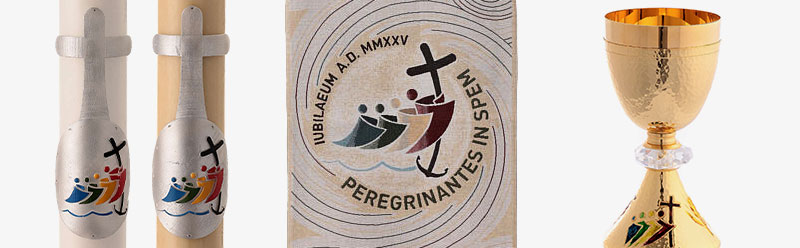

Even the collection of offerings in the church, the so-called begging, which aims to support the religious community and allow the parish to invest in works of charity for the poor and needy, is an essential form of almsgiving for those who believe and regularly attend the church. By giving something you show your willingness to share with other faithful and with anyone in need, sacrificing something that belongs to us for the common good. Not surprisingly, it takes place at the moment of the presentation of the bread and wine, in the process of becoming the Body and Blood of Jesus. The Sacrifice par excellence of Christ is joined by a small personal sacrifice of those who are preparing to celebrate the Eucharistic mystery.

To whom to give alms?

So must we give alms to everyone, without distinction? It is necessary to make conscious choices. No one should indeed be denied help and mercy in times of difficulty, but it is also true that it is not productive to justify and feed phenomena of begging and especially of exploitation of weaker and defenceless people, such as children or the elderly or the disabled.

Furthermore, we will have to learn to discern the real poor from those who, out of laziness or willful misconduct, do not want to work for a living, and are content with what little they can steal from good-hearted people. Woe to encourage certain behaviour!

Those who ask for alms should do so only out of actual necessity, not as a job, and it is a specific duty of a good Christian to know how to distinguish, also to be able to intervene to help differently those who, due to lack of knowledge of the country or simplicity of intellect, he desperately wants to work and he might as well, but he can’t find a way.

In any case, it will be important, in giving alms, to respect the dignity of those who receive it, guaranteeing a bond, a contact that goes beyond that exchange of coins. Shaking hands, looking, a kind word, even a caress, will be the most precious and pleasing form of charity not only for those who receive it but also in the eyes of God.