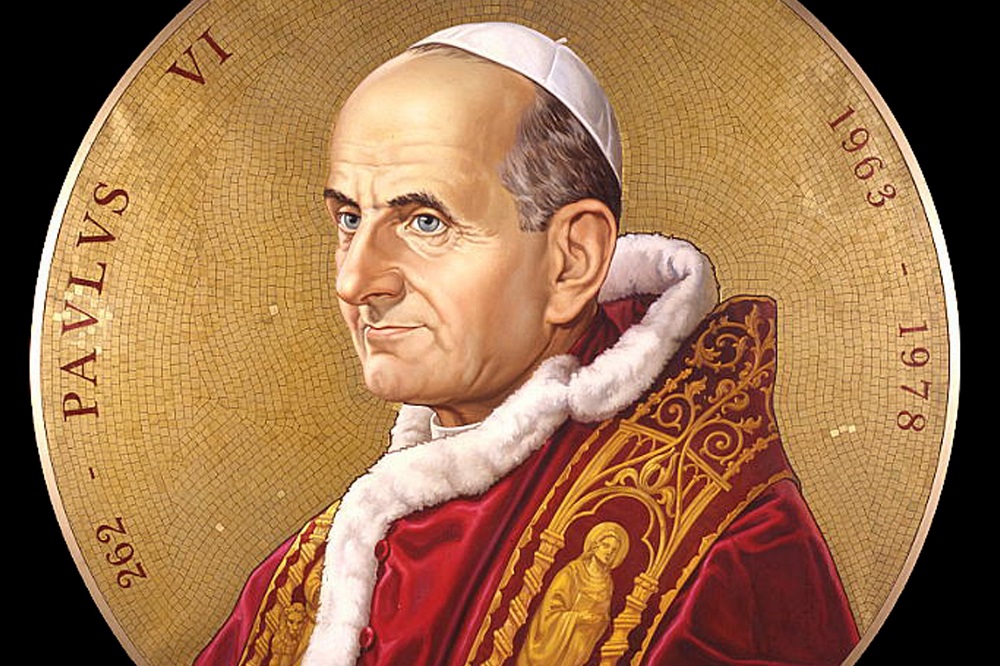

Pope Paul VI was a reserved and courteous man, with a refined intellect and great spiritual depth. He led the Catholic Church in a period of great change and knew how to combine tradition and renewal admirably.

Contents

It is difficult to think about how the Catholic Church could adapt to the modern world without losing its fundamental values and principles.

Pope Paul VI offers us an illuminating example of how this was possible, he was Supreme Pontiff between 1963 and 1978, and already joined his predecessors by playing roles of primary importance in the Italian and world religious scene.

Between the 60s and the 80s the world’s social and political reality changed radically, moving away in many cases not only from the legacy of values and social conventions that had been established in previous centuries but also separating itself from religion, from spiritualities. Think of the youth protest, which culminated in the 1968 uprisings, and led to the birth of alternative and secular cultures. But we cannot forget also the Cold War and the imposition of the communist ideology of a Marxist, secularist and anticlerical Soviet matrix, and terrorism, which in Italy manifested itself in the bloody actions carried out by groups of the extreme left and extreme right, such as the Red Brigades and the New Order.

The Church was still immersed in the events of the world, and yet her role required a change, to still allow her to intervene and make a difference. The famous phrase pronounced by Paul VI in 1968, when the wind of contestation threatened to completely overwhelm doctrines and dogmas: “We waited for spring, and the storm came”.

Even John XXIII, who preceded him on the papal threshold, tried to mediate the frictions between the Church and the new realities that opposed it, instituting the Second Vatican Council in 1962. The same Council was then carried forward by Paul VI himself, who reiterated the importance of faith and humanity as instruments of collaboration between church and world, and the church emerged reformed both internally and in its approach to modernity and other religious professions.

But in addition to external pressures that endangered the millennial integrity of the church, Paul VI also had to deal with internal problems, which made his authority falter. On the one hand, the ultra-radicals expressed their disagreement with any attempt at openness and modernisation, on the other the representatives of the clergy close to the socialist circles claimed the need for greater innovations, calling the Pope immobile. This led to continuous tensions between the Pontiff and the episcopal college, for the duration of his mandate.

If his predecessor John XXIII, to whom Paul was deeply bound by a relationship of mutual esteem and friendship, was a man open to the world, extroverted and close to the people, Paul VI was much more reserved and austere.

This did not prevent him from demonstrating great diplomatic and political skills, also thanks to the experience gained first as a senior official of the Secretariat of State, then as Archbishop of Milan and finally as Cardinal.

He was a courteous man, deeply humane, cultured and belonged to that Italian high bourgeoisie that had made the political and cultural history of the country at the turn of two centuries. A man apparently not suited to face the profound social and cultural revolutions of that time, yet, precisely thanks to his balance, able to hold the Church with a firm and sure hand through the storms of those turbulent years.

Life before becoming a Pontiff

Paul VI was born on 26 September 1897 in Concesio, north of Brescia, into the Montini family, which belonged to the upper bourgeoisie. He was baptised with the name of Giovanni Battista. His father Giorgio was a lawyer who ran the Catholic newspaper Il Cittadino di Brescia, and later he was a deputy in the Italian Popular Party of Don Luigi Sturzo. His mother Giuditta Alghisi belonged to the small local rural nobility.

He attended schools as an external student due to poor health at the college “Cesare Arici” of Brescia, run by the Jesuits. After obtaining his Classical diploma in 1916, he entered the seminary of Brescia as an external student.

In 1919 he became a member of the ICUF, Italian Catholic University Federation, of which in 1925 he would become a national ecclesiastical assistant.

He was ordained a priest on 29 May 1920, in the cathedral of Brescia.

He attended the university in Milan obtaining his doctorate in canon law, then in Rome to follow the courses of Civil Law, Canon Law, Letters and Philosophy. He also followed the courses of the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy and thus began to collaborate during the pontificate of Pius XI with the Vatican Secretariat of State, the body in charge of coordinating the various offices of the Holy See and relations with States and international organizations.

In 1923, he was sent for a year as an attendant to the apostolic nunciature in Warsaw, Poland, where he found himself facing the effects of local nationalism, which viewed foreigners with malice.

Returning to Italy, he obtained the three degrees and assumed the role of national ecclesiastical assistant of the ICUF, which he would leave eight years later, impatient with the continuous resistance opposed by the Jesuits and other representatives of the church regarding the difficult coexistence of the Church with fascism and the cultural and social changes underway.

In 1937, Montini was appointed substitute of the Secretariat of State and with this office he wrote the radio message read on 24 August 1939 by Pope Pius XII, meanwhile elected, to prevent the outbreak of the War.

During the war, he worked in the Vatican Information Office. He also participated in covert operations to hide and rescue thousands of Roman Jews. When at the end of the conflict the Pope was overwhelmed by the accusations of the Church’s behaviour towards Nazism he was not touched by them.

In 1944 he assumed the post of Pro-Secretary of State and continued to collaborate with Pope Pius XII, especially in defending the Catholic world from the spread of Marxist ideas.

On 1 November 1954, he was appointed Archbishop of Milan. As archbishop, he showed interest and closeness to the conditions of the workers and collaborated with unions and associations to improve them. He also started building dozens of new churches. He showed himself liberal and willing to dialogue even with schismatics, Protestants, Anglicans, Muslims and atheists, earning himself the reputation of a progressive.

On 28 October 1958, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, Pope John XXIII, a great friend of the future Paul VI, who was appointed Cardinal by him, ascended to the papal throne. With this new role, he travelled around the world as a representative of the Pope and was a member of the preparatory commission for the Second Vatican Council.

Pope from 1963 to 1978

After the death of Pope John XXIII, John the Baptist Montini was elected Pope on 21 June 1963, under the name of Paul VI.

Paul VI was able to support the modernisation of the Church without ever losing sight of the protection of the faith and the primacy of human rights, above all the defence of life.

He was the first pope to travel by plane, and this allowed him to travel to distant lands and have relations with statesmen and religious leaders. In particular, on the occasion of his first trip to the Holy Land in January 1964, he joined in a symbolic embrace with the Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople Athenagoras I, and this gesture led to the rapprochement between the two churches and to the drafting of the Common Catholic-Orthodox Declaration of 1965.

He was also the first pope in history to set foot in the UN headquarters, where he issued a heartfelt appeal for peace on 4 October 1965, broadcast worldwide. We are in the middle of the Cold War, the world is split in half by the Atlantic Pact (USA and pro-American countries) and the Warsaw Pact (satellite states of the Soviet Union).

Thus the Pope said to the representatives of the state present and the whole world: “You sanction the great principle that relations between peoples must be governed by reason, justice, law, negotiation, not by force, not by violence, not by war, nor by fear, nor by deception.”

In 1967 he also established the World Day of Peace, which was first celebrated on 1 January 1968.

As we mentioned earlier, Paul VI continued the work of his successor John XXIII by carrying forward the work of the Second Vatican Council, which ended in 1965. The highlights of this Council were:

- a better understanding of the Catholic Church;

- reforms of the Church;

- advancement in the unity of Christendom;

- dialogue with the world

In particular, the reform of the liturgy already begun by Pius XII (1939-1958) was implemented with further innovations. Already with Pius XII the use of the vernacular was allowed for baptisms, funerals and other events. After the Vatican Council, in 1969, although the Missal had not undergone any particular changes, the “new Mass” in the national language was approved by Paul VI. The Tridentine continued to be celebrated in Latin.

In addition, the Sacrosanctum Concilium required the priest to administer the Mass to the faithful (versus populum) and no longer to the east (ad Deum).

The introduction of folk and modern music into liturgical celebrations was allowed until then fiercely rejected.

Still, in 1966, Paul VI abolished the index of forbidden books, maintained for over four hundred years and supported by the most conservative clergy.

He also revolutionised the papal elections, establishing the maximum age of 80 years for participation in the Conclave and limiting the ostentatious pomp on the occasion. Paul VI eliminated many ornaments that had distinguished the Papacy for centuries, going so far as to substantially modify the ceremony of the papal coronation.

On the other hand, however, he reiterated what was established by the Council of Trent regarding priestly celibacy, with the encyclical Sacerdotalis Caelibatus of 24 June 1967, and supported the traditionalist position regarding contraception, reiterating in the encyclical Humanae Vitae of 25 July 1968, what was already declared by Pope Pius XI, that it was illegal for Catholic spouses to use contraceptives of a chemical or artificial nature.

Paul VI also had the merit of attributing the title of Doctor of the Church to Saint Teresa of Avila on 27 September 1970, with the Apostolic Letter Multiformis sapientia Dei, and to Saint Catherine of Siena, on 4 October 1970 with the Apostolic Letter Mirabilis in Ecclesia Deus. They were the first women to obtain this qualification.

When St. Paul VI is celebrated

Pope John Paul II opened the diocesan process for the beatification of Paul VI. In fact, the Pope had been attributed two miracles, one linked to the healing of a child who should have been born with physical problems, the other always to a child born with a difficult and apparently desperate birth.

Paul VI was beatified on 19 October 2014 by Pope Francis. Again by Pope Francis on 25 January 2019, he established the liturgical memory of St. Paul VI on 29 May, the day of his priestly ordination.

The Papal Encyclicals

Among the various encyclicals written by Paul VI, in addition to those we have already mentioned, two are dedicated to Our Lady. This is the encyclical Mense Maio of 29 April 1965, which invites the Virgin to pray for the happy outcome of the Vatican Council and peace in the world, and the encyclical Christi Matri of 15 September 1966, a new invitation to the faithful to address their prayers to Our Lady to guarantee peace in the world. The devotion and imitation of the Mother of Christ were fundamental for Paul VI, who went so far as to affirm that the Mary-Church relationship was an integral and indispensable part of the divine Plan.

The Apostolic Exhortation Signum Magnum of 13 May 1967 deepens this relationship and underlines Mary’s role as Mother not only of Jesus but of Christians of all times.

From Eve to Mary: the figure of the Mother in the Bible

The mother, pillar of every family, beating heart and source of life for those who gravitate around her…

Here are all the encyclicals published by Pope Paul VI:

Ecclesiam Suam (His Church) – 6 August 1964.

Pope Paul VI’s pontifical manifesto focused on the Catholic Church and how he intended to carry out his mandate.

Mense Maio – 29 April 1965.

An invite to devotion to Mary in May for the successful outcome of the Vatican Council and peace in the world.

How to pray for grace in the Marian Month

May, the month of love has always been dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Let’s find out how to pray for grace in this special month…

Mysterium fidei – 3 September 1965.

Focused on the doctrine and worship of the Eucharist.

Christi Matri – 15 September 1966.

I invite Christians to invoke Mary in October for peace in the world.

Populorum Progressio (The Development of Peoples) – 26 March 1967.

Dedicated to cooperation among peoples and the problem of developing countries. The Pope denounced the worsening imbalance between rich and poor countries, neo-colonialism, capitalism and Marxist collectivism. On the other hand, he proposed the creation of a world fund for aid to developing countries.

Prierdotalis Caelibatus (Priestly Celibacy) – 24 June 1967

In this encyclical, Pope Paul VI defends the tradition of the Latin Church regarding celibacy to priests.

Humanae Vitae – 25 July 1968

The last encyclical written by Pope Paul VI defines the doctrine of marriage and reaffirms the procreative purpose of the conjugal act, refusing contraception between spouses.